Ambidexterity is the ability of being equally skilful with each hand. Attaining ambidexterity is crucial to any individual who must depend on a weapon for survival because in real combat, you are doomed if you can’t wield your stick, knife or gun proficiently with your other hand the moment your dominant hand got injured.

The ancient Greek physician Plato, considered the father of Western medicine encouraged people to train for ambidexterity, “Practice all the operations, performing them with each hand and with both together – for they are both alike – your object being ready to attain ability, grace, speed, painlessness, elegance and readiness.”

On what defines handedness, modern science has this to say: “There tends to be no real difference in the strength or dexterity of the hands themselves. The main reason for handedness lies in hereditary factors that determine which side of the brain will be more developed and therefore dominant. Typically the left side of the brain controls the left side of the head but the right side of the body. Likewise, the right side of the brain predominantly controls the right side of the head but the left side of the body. This is because the nerves crossover at the back of the neck. Thus people with a dominant left side of the brain tend to be right handed, In fact, 97% of right handers are left-brain dominant. Contrary to what might be expected, 68% of left handers are also left-brain dominant. About 19% of lefties and 3% of righties are right-brain dominant. About 12% of lefties (close to 1% of the total population) show about equal dominance on both sides.” (from What’s Right Is Right by David A. Gershaw, Ph.D.)

Being ambidextrous is an esteemed quality among fighting escrimadors. An excerpt from the life story of the late Leo Giron in Dan Inosanto’s The Filipino Martial Arts reads, “One of his instructors, a man the people called Mr. Delgado, used to travel from camp to camp to fight their best escrimadors. He was good, Giron remembers, and he could fight with either hand.”

In arnis, escrima and kali, the most fundamental way of attaining ambidexterity to practice double stick drills like sinawali. In these drills, the weak hand is developed by teaching it to borrow the movements of the dominant hand. There are designated roles for the dominant hand and the weak hand (often called the “alive hand” because it’s never idle) in the Filipino martial arts. “If he were wielding a single weapon, the alive hand would be the one that didn’t have a weapon. If he were wielding a long and a short weapon, the alive hand would be the one with the shorter weapon. If he were empty-handed or wielding two equal-sized weapons, the alive hand would generally be the one that come to play second,” wrote Inosanto in The Filipino Martial Arts. Training your weak hand to become as functional as your dominant hand in combat means reversing these roles during practice.

A good way to start is by practicing the basic angles of attack with your weak hand. Begin by just achieving the proper form then later on practice each angle of attack separately with speed and power. Having attained proficiency in delivering individual strikes, advance to practicing techniques in combination. With that achieved, the next stage could be fine-tuning your form and flow by doing carenza or shadow fighting with your weak hand. Finally, just like in training the dominant hand, the final stage should be to spar using your weak hand.

It is good to take note of the development of specific attributes so you can fully gauge if your weak hand is catching up with the abilities of your dominant hand. First of these is power. Can you hit as hard or nearly as hard as your dominant hand with your weak hand? Is there a great difference in gripping strength between your left and right hands? How about speed and accuracy? How fast and accurately can you hit a target with your weak hand as compared to your dominant hand?

Besides intentional training in specific martial arts skills, another way of increasing your ambidexterity is by using your weak hands more often in simple everyday tasks like opening a jar, pouring a drink or reaching for things.

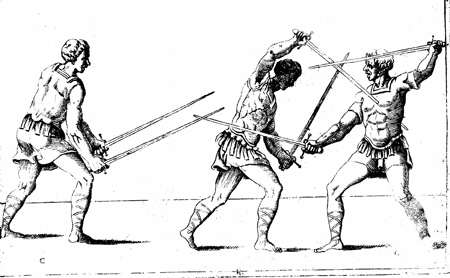

Not surprisingly, the quality of ambidexterity was also given importance by the old masters of Western swordsmanship (some aspects of arnis, escrima are borrowed from Western swordsmanship). A part of the book The Sword Through the Centuries by Alfred Hutton, reads, “From its not being an article of everyday wear, it [double sword] and its practice escaped the notice of most people, but it did not escape that of the leading professors of fence. They taught it, they teach the cultivation of it, and explained its method in their published works, and they earnestly advised their pupils to take up its study, on account of the advantage which a knowledge of its use would give them if engaged in a serious affair. Regardless as a game to be played in the sale d’ armes, the case of rapiers is more interesting than even the picturesque fight of the rapier and dagger, for in the latter the arms consist of a very long sword and a short dagger, and the player is therefore obliged to fight all through his bout as either a right-handed or as a left-handed man; but when provided with the ‘case,’ owing to the two swords being of moderate length and of equal size, he is in a position to change from right hand to left, or left to right, as the need to do so may flash across his mind, and that without the necessity of shifting his weapons, thereby altering instantaneously and radically the scheme of his play, and compelling a similar though unintended change in that of his adversary.”