While it is not highlighted in Philippine history, the first Filipino martyr for freedom was a Pampango, a Macabebe in particular. When Spanish forces under the leadership of Don Miguel Lopez de Legazpi landed on the shores of Manila in June 1571, the Tagalog chiefs namely Rajah Matanda, Lakan Dula and Rajah Soliman welcomed them.

When Legazpi sent out word to the chiefs of the surrounding country demanding that they too pay allegiance to the king of Spain, it was a Macabebe who raised a fist of defiance against the invaders.

The late National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin in his book “Manila, My Manila” wrote the following account on the Macabebe chieftain, “One Pampango headman, the king of Macabebe, exploded with fury upon being invited to do so.

He called on the chieftains of Pampanga to join him in driving the foreign devils away. A fleet of 40 warboats was assembled, each equipped with cannon. Down Pampanga River sailed some 2,000 troops, led by Lakan Macabebe himself.”

Another interesting part of Joaquin’s book is the part that describes how the Macabebe chieftain treated Legazpi’s envoy, it reads, “Up jumped the king of Macabebe, drawing his sword. ‘May the sun split my body in half,’ cried he, ‘and may I become shameful and hateful in the eyes of my women, if ever I befriend the Kastila!’

And brandishing his sword at the Spanish officer, he yelled: ‘Tell your master we have come to make war, not peace, and are challenging him to meet us in battle on the waters of the bay!’ After which he jumped out the window and fled to his boat.”

The king of Macabebe (sometimes referred to as Tarik Soliman or Bambalito by historians) perished in the Battle of Bangkusay on June 3, 1571. While they were the first to defy Spain, the Pampango warriors, known for their courage and skill in battle later on fought side-by-side with the Spaniards as mercenaries.

They fought against the Chinese pirate Limahong, the Moros, the Dutch and the British. Describing the feral courage of the Pampango warriors, Gen. William Draper, head of the British fleet that captured Manila in 1762 wrote, “They never retreated and they fought like mad dogs, “gnawing at our bayonets.”

Noting the long collaboration between the Pampangos and the Spaniards, historian Dr. John Larkin wrote, “Throughout the Spanish Period, even until the early American Period, Kapampangans loyal to Spain (especially those who fought for Spain) were referred to as Macabebes, even if they came from, for example, Arayat or Candaba or Bacolor.”

Fray Casimiro Diaz, a historian of the Augustinian order, referred to the Pampangos as, “the most warlike and prominent people of these islands. [Their rebellion] was all the worse because these people had been trained in the military art in our own schools, in the fortified posts of Ternate, Zamboanga, Jolo, Caraga and other places where their valor was well known.”

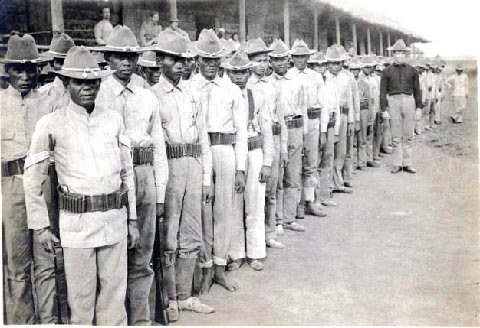

The warrior and mercenary culture of the Macabebes was still evident during the American period. The infamous Macabebe Scouts formed the backbone of the Philippine Scouts that was later to become the Philippine Constabulary. While feared as mercenaries, the Macabebes also earned the unsavory reputation of being treacherous because of the military services they have rendered to foreigners.

It is interesting to note that 81 Macabebe Scouts participated in the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo, the first President of the Philippine Republic in Palanan, Isabela on March 1901. In defense of the mercenary culture of the Macabebes and commending their exemplary military skills, Professor Randy David of the University of the Philippines Diliman said,” It was a way of rebelling against the inferior status to which colonialism has consigned them as indios.”

Land of the blades

Various archeological diggings in Pampanga in 1930, 1959, 1960 and the 1990s yield evidences that an extensive community thrives in the location decades before the Spaniards came in 1571. An article written by Joel Pabustan Mallari for the Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies reads, “Also discovered were chinaware shards, postholes and metal implements, 15 pieces of which were metal blades used for agricultural and ceremonial activities. Some resembled sundang and talibung (bladed weapons) and spear points. Mallari also named a “heat and hammer” bladesmithing method native to Apalit, Pampanga called “pukpuk.”

Expounding on the sophisticated metallurgical knowledge of the Pampango bladesmiths of yore he wrote, “In Apalit, it is said that the source for the steel comes from the black sand common to Capalangan. This sand, which some old folks also call kapalangan, is magnetite sand, the source of high-grade iron.

Although this kind of iron sourcing requires a higher metallurgical skills and pyrotechnology just like in the ancient production of Japanese katana.” Capalangan is a barrio in Pampanga whose name can be roughly translated as “land of palang.”

“Palang” is a kind of sword similar to the parang of Mindanao and the parang or pedang of Indonesia. Mallari even mentioned a method of forging endemic to the province, “This old method of forging called ‘pituklip’ or folding and ‘subu’ the forging with the hard and soft steel, which are from the early tradition of carburization process were practiced earlier in the region.”

Panday Pira, the famous Filipino metallurgist that lived between 1483 to 1576 was said to be a resident of Barrio Capalangan. Panday Pira was credited for inventing the lantaka, a small cannon that could be rotated and maneuvered at any angle during battle.

The Majapahit Empire (1293-1527) that spans most of Southeast Asia including the Philippines was once known for its skilled bronze cannon-smiths. Panday Pira initially made weapons for Rajah Soliman but was later commissioned by the Spaniards to make cannons for their ships and the fortification of Intramuros.

Style of arnis-escrima

Pampanga is known as the home of sinawali or the double stick fighting methods of arnis-escrima. The etymology of “sinawali” came from the word “sawali,” a panel of woven bamboo skin used as walls of nipa huts. The crisscrossing weaves of the sawali resembles the intricate movements of the double sticks hence the term. The concept of fighting with weapons in both hands is not limited to stick fighting but is translatable to knife and sword fighting.

The unique Pampango method of weapons fighting is still practiced today as an independent style or as a part of a particular system of arnis-escrima. A good example is the style taught by the late Grandmaster Leo Giron. Giron’s method is comprised of 20 different styles of fighting and one of these is the Estilo Macabebe or double sticks style.

In an article titled “The Evolution of Arnis,” the late FMA scholar Pedro Reyes mentioned a unique characteristic of the Macabebe style, he wrote, “One such is the Macabebe Style, named after a town near Manila, the Philippine capital. Its adherents swing and twirl their batons in complicated circles and figures of eight.”