I like things that work. This is primarily the reason why I was drawn to arnis, escrima and kali collectively known as Filipino martial arts (FMA) in the first place. The FMA was originally a battlefield art, which explains its no-nonsense practical approach to combat.

Another thing I like about the FMA is that it is a continually evolving art. With constant evolution as a guiding principle, I am constantly on the look out for new technologies that could be integrated into the FMA framework to enhance its efficacy.

One of the exemplary works I mentioned in my previous writings that could benefit FMA practitioners immensely was Tony Blauer’s research on the startle response or primal flinch. Based on Blauer’s findings, a human being’s reaction 100 percent of the time whenever he sees threat coming his way is to flinch–bringing his arms up in an attempt to push the danger away. Because knives were commonly used in ambushes, I believe that the integration of the startle response into FMA blade training will make it more effective.

Another excellent work that caught my attention in recent years was Tim Larkin’s Target Focus Training (TFT). Larkin’s TFT has a simple objective and that is to teach how to use violence as a survival tool. The one element of TFT that I believe would serve FMA practitioners well is its teachings on injury and how it affects the outcome of a fight. I could easily relate to this concept because the weapons of the FMA right from the get-go are meant to inflict injuries.

TFT teaches that injury is the turning point in every fight. The TFT people by the way define injury as “debilitating trauma,” meaning something was ruptured or broken inside the body and for it to get fixed requires medical intervention.

Citing forensic data, the TFT people point out that in actual cases of violent confrontations, the individual inflicting the injury on the other party was the one who walked out of the encounter alive.

To quote Larkin, “In violence, the person who lands the first injury is usually the person that walks away as the winner. So your focus in an asocial violent attack is to get an injury on the other guy, period… then continue to injure him/them until he/they are non-functional. (The Tool of Violence, interview by Ben Stone published in Blitz Australasian Martial Arts Magazine, October 2011).”

And it was here that I realized the strong connection between TFT and FMA. It may turn off a lot of people but the weapons of the FMA require a killing commitment or to a lesser degree the readiness to inflict serious injury. This is not an arrogant or a “macho” statement but simply an acceptance of the true nature of the FMA. The realization of this truth will not only heightens a practitioner’s chance of survival in actual combat but will also increase his respect for life and his abhorrence of senseless violence.

Arnis master Prof. Armando Soteco told me many anecdotes on how, before arnis was declared the Philippines’ national martial art and sport through a law, many Physical Education specialists have had second thoughts on teaching arnis in schools because of the inherent danger of weapons training. It was also that dilemma that challenged Soteco to perfect a method of teaching arnis safely to very young children.

Another chilling lesson I learned from TFT’s teachings is that an injured person is helpless. How terrifyingly true. Regardless of the level of your skill as a martial artist, you are helpless once your opponent succeeded on injuring you seriously.

I believe that the failure to embrace the true nature of violence is the reason why many skilled martial artists were vanquished by criminals. It was not lack of skills that caused their downfall but their wrong mindset – the criminal is operating with a full intent to inflict lethal injury while the typical martial artist aims to “control” the attacker.

TFT simply recognizes the fact that to survive a real life-or-death encounter, one must enter it with the same level of violence that criminal sociopath brings on the table.

Recently, a martial arts colleague asked me to demonstrate carenza (escrima shadow fighting) with a blade to a new student.

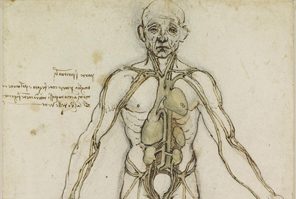

I obliged and after the demonstration answered their questions on the supposed meanings of my movements. I told my colleague and the young student that to me, “intent” is important when performing carenza and that my moves were directed toward the anatomical targets of my imaginary foe. I explained that the slashes were directed toward exposed arteries (carotid, brachial, radial and femoral). The thrusts I said were aimed at specific internal organs. I later learned that the young student is a nurse and I advised him that reviewing his anatomy textbook would make his FMA more functional. If inflicting serious injury is the goal then one must know the location and vulnerability of your targets.

The FMA is an effective art because it recognizes the true nature of violence. In a life-or-death encounter, be the one delivering the violence not the one receiving it.