Terrain will affect the way you fight. An escrimador unaware of this fact is bound for a rude awakening when he finds himself fighting in an unfamiliar environment.

Terrain changes everything. If your fight plan is based solely on fancy footwork, all you have to do is to practice on the slope of a hill or on a slippery surface to discover that it just won’t work

“It’s easy to develop preferences, especially when all your training is done in ideal situations where you can select whatever methods suits you, but when the real thing occurs chances are the ideal situations won’t be present,” wrote Dan Inosanto in “The Filipino Martial Arts.”

You don’t know when and where a real fight would occur and the best way to avoid unpleasant surprises is to cover all possible scenarios in training as much as you can. It’s OK to perfect your favorite techniques but always have a plan B and a plan C just in case.

A largo mano (long hand or long-range fighter) exclusively skilled in scoring hits with the tip of the stick from a distance would be in trouble if he ends up fighting in confined spaces.

The escrima stick has three parts that can be used to inflict damage depending on combat range. The first part is usually employed at long range while the other two were used at close range.

The first part is the business end of the stick – the first three inches from tip. This is the part that travels fastest and is most useful in hitting targets from long and middle range. The next part is the shaft, which is the section between the tip and the grip.

The shaft is useful in doing takedowns, throws as well as locks and chokes at close range. The last part is the butt of the stick or punyo (the Spanish term for fist). The punyo can be use to hammer, scrape or dig on the opponent’s anatomy at close range.

An example of the lethal use of the punyo is the Dog Brothers’ fang choke technique wherein the butt of the stick is systematically placed and pressed against the opponent’s throat.

Prepare for both urban and jungle settings. In the former, fighting through doors, different heights of embankments and low ceilings are the primary concerns while in the latter, foliage, ground characteristics (muddy, rocky, inclined) and natural obstructions should be the main considerations.

An escrimador can use the structures in a particular environment against his opponent. For instance, he may entice his foe to strike in a certain way so his weapon could hit a concrete wall and break against it.

If you’re in a grappling situation on a hard surface, you can trip or throw your attacker, purposely landing him on his head to injure the brain or neck (this technique is justified only in situations where your life is in grave threat).

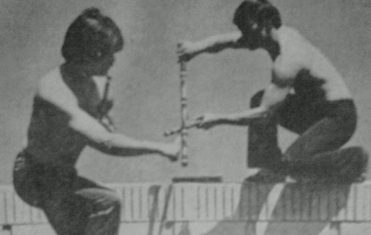

Drills therefore should be practiced on different positions – standing, squatting or lying. The fighter’s aim in all three positions is to maintain weapon control as well as power, speed and accuracy.

Knowing which types of strikes would fit into the available fighting space would also stack the odds on your favor. Generally speaking, vertical strikes would work well in an upright rectangular space (fighting through a doorway for example) while horizontal strikes are best used when fighting in a rectangular space that is parallel in orientation.

Diagonal strikes done in an X-pattern as well as thrusts would function well in both scenarios. A fighter can tighten the X-pattern for vertically oriented spaces and widen it for horizontally oriented spaces. In addition, snapping hits are more practical to use than follow-through strikes when fighting in cramped spaces.

A modern day escrimador might find the idea of fighting beneath a low ceiling farfetched but during the olden days in the Philippines, such scenario is not unlikely.

The Filipinos of yore usually kept livestock like chicken, goat or pig beneath their houses or the “silong” in Tagalog. A fight could occur in these confined spaces the moment, the owner of the house caught a thief in the act of stealing his animals.

In ending, I would like to use another quote from Inosanto’s book offering advice on variable weapons, “I said before that an escrimador should be able to pick up any weapon and wield it.

Since we’re talking about environments, you might remember that when an encounter occurs, chances are you won’t have your weapon with you and if your opponent has a weapon, he has an advantage.

A good environmental exercise might be, then, to pick up objects around you and practice with them. You never know when a shoe or a rolled-up newspaper may all you have to stop a knife or a tire iron.”