Savage as they may seem in the eyes of Westerners because of their headhunting tradition, the Bontoc Igorots of Northern Luzon follows elaborate conventions of warfare. The Igorots were a warlike people before the majority of them were Christianized. A tribal war usually starts after a tribesman took the head of a member of another tribe. Taking heads during earlier times was a rite of passage among Igorots and was often initiated by tribesmen who intend to marry.

En-fa-lok′-nĕt is the Bontoc term for war but the expression “na-ma′-ka,” which means “to take heads” can be used as a substitute for it. If one tribe was offended by a beheading, it can demand retribution. Albert Ernest Jenks, in his book “The Bontoc Igorot” published in 1905 wrote, “It now and then happens that of two pueblos at peace one loses a head to the other. If the one taking the head desires continued peace, some of its most influential men hasten to the other pueblo to talk the matter over. Very likely the other pueblo will say, “If you wish war, all right; if not, you bring us two carabaos, and we will still be friends.” If no effort for peace is made by the offenders, each from that day considers the other an enemy.” The ceremony where the peace offering was brought to be shared by both parties is called “pwi-dĭn.” Jenks noted that the accord is sealed with an exchange of articles with the people sued having the better part of the trade.

To break such treaty, another ceremonial meeting called “mĕn-pa-kĕl′” must be held. After the elders of the tribe decided on the matter, a messenger is sent to the other camp bearing a battle-ax or spear. These weapons, Jenks explained, is “the customary token of war of the Bontoc peoples.” The messenger then must present himself to any old man of the rival tribe and say, “In-ya′-lak nan sud-sud in-fu-sul′-ta-ko,” which translates, “I bring the challenge of war.” On the safety of the messenger, Jenks wrote, “The life of the war messenger is secure, but, if possible, he is a close relative of the challenged people. There is no record that such a person was ever killed while on his mission.”

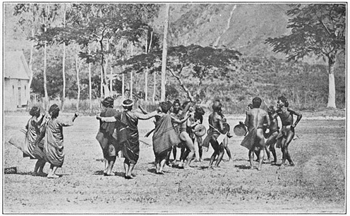

A group of Igorot men performing a war dance (from the Project Gutenberg).

Jenks observed that a challenge is almost always accepted. To show their intent of accepting the challenge, the challenged tribe hand over an ax or spear to the messenger. The latter then returns to his community and shouts, “Ĭn-tang-i′-cha mĕn-fu-sul′-ta-ko,” which means, “They agreed to fight in war.”

Nearly all men of both sides will participate in a battle within a few days. They will appear in an opportune place shouting challenges at one another. Peace is still possible at this stage if one party decided to capitulate. If that happened, the camp desiring peace will send a messenger with an offering of a pig or chicken. Friendship is restored if the offerings were accepted, if not, all hell breaks loose.

Jenks has vivid description of Igorots in the heat of battle, it reads, “Men go to war armed with a wooden shield, a steel battle-ax, and one to three steel or wooden spears. It is a man’s agility and skill in keeping his shield between himself and the enemy that preserves his life. Their battles are full of quick, incessant springing motion. There are sudden rushes and retreats, sneaking flank movements to cut an enemy off. The body is always in hand, always in motion, that it may respond instantly to every necessity. Spears are thrown with greatest accuracy and fatality up to 30 feet, and after the spears are discharged the contest, if continued, is at arms’ length with the battle-axes. In such warfare no attitude or position can safely be maintained except for the shortest possible time.”

In addition to battle axes and spears, Jenks mentioned another weapon used by the Igorots in combat, “Rocks are often thrown in battle, and not infrequently a man’s leg is broken or he is knocked senseless by a rock, whereupon he loses his head to the enemy, unless immediately assisted by his friends.”

Such battles, lasting about 30-minutes to an hour, often ceases after the taking of a single head by either side. But there were cases when fights last for half a day and ten or dozen heads were taken.

One interesting part of Jenks accounts is how firearms affected the way of warfare of the Igorots, it says, “Seven pueblos of the lower Quiangan region went against the scattered groups of dwellings in the Banawi area of the upper Quiangan region in May, 1902. The invaders had seven guns, but the people of Banawi had more than sixty—a fact the invaders did not know until too late. However, they did not retire until they had lost a hundred and fifty heads. They annihilated one of the groups of the enemy, getting about fifty heads, and burned down the dwellings. This is by far the fiercest Igorot battle of which there is any memory, and its ferocity is largely due to firearms.”