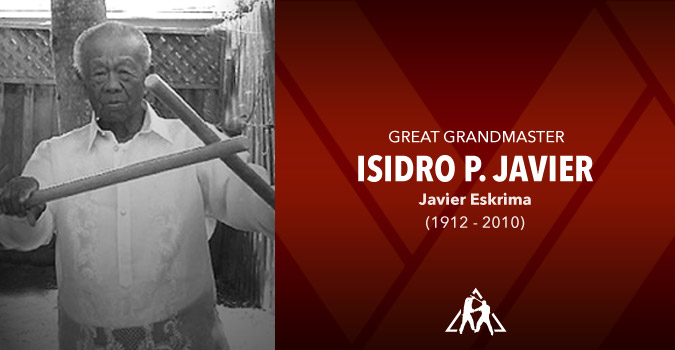

Isidro Javier began his life’s journey in Tagudin, the Philippines, May 10, 1912. Life in the “Barrios” or Barangays of the city found families and clans bundled together in closely guarded camps, each with their own dialects, rules, and protection.

Competition often turned to violence as each Barrios jealously guarded its territory. Isidro Javier learned to be his own master in the toughest school of all; real life and death combat in the streets, grooming him as a leader and preparing him for the challenges he would face.

Isidro’s father was a maker of nets, done by hand, a craft that was handed down generation after generation. And so was the ancient and secretive art of Eskrima and the Bolo Knife, known in the western world as Filipino Bladed Art (FMA) Filipino Martial Arts.

Fathers taught their sons how to make weapons from the simplest of tools, and as a boy, young Isidro practiced his family art in the streets with his friends and ultimately, against his enemies.

Saturnino Javier

In an interview, Mr. Javier described himself as a “troublemaker”, and recounted how he was the leader of his gang of six boys. The gangs clustered in small groups for protection and the constant give and take of power and territory. The boys practiced Eskrima every day, perfecting their techniques, mastering new moves, always in the quest to top the competition.

There were no Dojos, no nicely padded mats, helmets or body protection. They simply whacked each other black and blue with the sticks which easily raised lumps and bruises, but Isidro Javier decided the knife was his weapon of choice.

They would wrap their wrists with shirts or cloth and slice at each other in whirling, flashing moves. The result often meant cuts and slashes on the wrists and arms, but then, “the girls come and dress the wounds”.

“Sometimes there was no time to wrap the wrists,” meaning if a fight broke out with another gang; they would go at it with no protection at all. Mr. Javier shows the numerous scars on his wrists from real street combat.

To be a gang leader, one had to show absolute fearlessness, total confidence and be the best with stick and knife. Isidro Javier was all of that. “Fight because of girls. When I say I want that girl…no touch that girl. No good to fight if no encouragement (from the girls).”

But the fighting became so dangerous that the local Priest intervened and forced the boys to swear not to fight. Mr. Javier smiles and doesn’t reveal whether the fighting really stopped.

For many boys of Tagudin, the only life was what they made in the streets, but for Isidro Javier this would never be enough. His keen mind and restless spirit could not be confined to the world he was born into.

When he was only thirteen years old he borrowed a friend’s driver’s license, lied about his age, and bought the Cidual Tax required for anyone who wanted to leave the Philippines. He sailed to the big island of Hawaii and went to work on the sugar plantations, then to the other islands to harvest Pineapple.

But opportunity soon knocked when his older brother Manuel bought his plane ticket and brought him to Pismo Beach, California. Isidro was the only one in the family who went to high school, and Manuel needed a bookkeeper to run his sugar pea farm.

But war came to America and to Isidro’s homeland when the Japanese launched their master plan of Busido (Divine Right), and soon, Javier found his way into the Navy on an aircraft carrier in 1943.

Isidro was one of only four men assigned to fuel the aircraft on ship, and during combat he manned a machine gun as Japanese torpedo and Kamikaze planes attacked.

His ship, USS Nehenta-Bay (CVE-74) sailed and battled in the South Pacific, but survived un-damaged through several campaigns. Isidro Javier earned his medals and his U.S. Citizenship, and returned as a hero.

(Victory Medal WWII – Silver Star, Asia-Pacific Campaign Award – Silver Star, Philippine Liberation Award – Star)

However, Isidro Javier’s inner drive would not allow him to remain under his brother’s wings for long. Over the years he became a driving force that helped shape the Filipino community. He farmed, fished, and raised and trained prized roosters, which was a popular pass time of the community.

On July 23, 1946 he earned the all-time record fish catch in Pismo Beach when he landed twenty-three tons of fish in one day.

Javier bought farmland all around the Central Coast and his status as a leader in the Filipino Community grew.

In the 1960’s the Farm Labor Movement brought Caesar Chavez to “Manong” (Godfather) Isidro Javier’s home, which became headquarters for the farm laborers as they fought for better pay and work conditions.

Manong Javier worked side by side with Caesar Chavez as his main organizer. “I told them (workers) what to do, and they did it… I made things happen”.

Even in his golden years, Mr. Javier has his hand on the pulse of the Central Coast and commands great admiration from the community leaders.

Numerous awards including his advancement to 33rd Degree in the Masons, mark Isidro Javier’s many accomplishments.

His remarkable good health can be traced through a life of proper nutrition and diet. Mr. Javier is a master cook with some highly sought after secret recipes.

Isidro Javier has had a life filled with achievements that are far removed from fighting in the streets of Tagudin, a life that has met the world head-on and remains the victor.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.