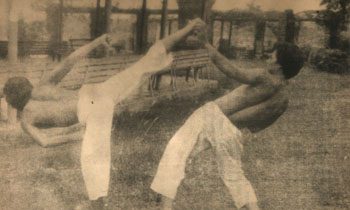

I first witnessed demonstrations of sikaran or Filipino foot fighting during the early 1990s; the first was in a martial arts festival held at the Metropolitan Theater in Manila and second during my visit to its birthplace, the town of Baras in Rizal province. Sikaran’s kicking is as flamboyant as that of tae kwon do though the delivery is less artistic and more rugged.

Sikaran’s etymology came from “sikad,” which is the Tagalog word for kick (sipa and tadyak are also alternative Tagalog terms for kick). Thus sikaran literally means, “To exchange kicks.”

Unlike the Filipino stick and blade arts, sikaran did not originate as a battlefield art but only as a mere sport. Nid Anima in his book “Filipino Martial Arts (1982)” wrote of the origin of this native style of foot fighting, it reads, “Sikaran’s inception has been placed at around 1900, a pastime of the Baras (Rizal) farmers whose wont had been to kick one another before going to work in the fields.

Doing it constantly made them develop skills that would eventually be marked by effectiveness such that other martial arts could hardly compare, or so claims its most ardent exponent.”

Sikaran today has adapted elaborate sporting rules many of them borrowed from other Asian martial arts like karate but in its original form the conventions of the game is very basic as described by Anima in the following words, “A sikaran session commences with the drawing of a circle on the ground.

The acknowledge talent of the lot, by reason of his superior skill, is often obliged to concede a handicap, thus he positions himself inside the circle and trade kicking talents with the one who stays at the circle’s rim. The objective is for the combatant outside to dislodge the contestant within. The rules are really that simple.”

With the same rules applying, a variation of the above is for a group of men to form a circle and allow the match to commence inside it.

Hands in traditional sikaran were not utilized in offense but only in parrying and blocking kicks. In the original set-up, no time limit is observed and participants may call for a time out if he’s too exhausted or is willing to give up. Men and women are welcome to train.

The kicking style of sikaran displays the same mechanics as that of other martial arts. The delivery can be frontal, sideways, spinning, upward or downward, snapping or follow-through as well as on the ground or jumping. Anima on the kicking repertoire of traditional sikaran wrote, “If kung fu has its various styles of fighting in the praying mantis, white crane, tiger claw and monkey axe, among others, so does the sikaran have its own share of kicking styles in the biakid (similar to the karate reverse roundhouse), padamba (jumping front kick), pilatik (front snap kick) and tuhod (knee blow).

The most conspicuous sikaran techniques are identified as pilatik-rap (front kick), pilatik-lid (side kick), pilatik-kod (back kick), pilatik-kot (roundhouse kick) and pilatik-pad (flying kick). Of these all, the pilatik-kot according to the masters, seems to be the most formidable to parry.” In all these, two general classifications were followed; panghilo (kicks that aims to dizzy or paralyze the opponent) and the pamatay (lethal kicks).

If karate has Mas Oyama who became famous for his incredible tameshiwara (breaking) skills and for slaying bulls with his bare hands, sikaran boasts of its own roster of legends. Another part of Anima’s book reads, “They have a venerable name for a master, “hari (king),” whose equivalent is perhaps judo’s 10th dan holder.

One such hari is Perfecto Ballesteros, alias Agila (for his impressive agility), acknowledge as the foremost padamba (jumping front kick) exponent. That he could leap as high as 10 feet is definitely a testimony to an awesome power. So also was Alfonso Tesoro classified as hari, a fellow refuted to crack husked coconuts with his steel-like shins.

Hari Pedro Castañeda, on the other hand, boasts of the singular reputation of killing a carabao with a single biakid.” But it was Col. Meliton Geronimo who has brought sikaran to the martial arts mainstream. Geronimo who has been an active competitor in the karate tournament circuit during the 1960s reached the height of his popularity during the 1990s because of his effort to promote sikaran in the Philippines and abroad.

In conclusion, it is interesting to note that a similar sport of foot fighting was documented by a foreigner in the northern part of the Philippines at the same time of the supposed inception of sikaran in Baras. Albert Ernest Jenks, in his excellent book “The Bontoc Igorot,” (Manila 1905) wrote of a unique pastime of the Igorots, it reads, “The other game is kag-kag-tin′.

It is also a game of combat and of opposing sides, but it is not so dangerous as the other and there are no bruises resulting. Some half-dozen or a dozen boys play kag-kag-tin′ charging and retreating, fighting with the bare feet. The naked foot necessitates a different kick than the one shod with a rigid leather shoe; the stroke from an unshod foot is more like a blow from the fist shot out from the shoulder.

The foot lands flat and at the side of or behind the kicker, and the blow is aimed at the trunk or head—it usually lands higher than the hips. This game in a combat between individuals of the opposing sides, though two often attack a single opponent until he is rescued by a companion. The game is over when the retreating side no longer advances to the combat.”