Within farming communities in the Philippines even today, both young and old wear a bolo on their waists. It is amazing to watch the precision of these people as they use their bolos to unhusk a coconut or split a bamboo as if the blade is an extension of their limbs. Even in urban areas, most Filipino households own a bolo because of its excellent utilitarian purpose.

The common distinguishing characteristic of the bolo is its blade that widens and curves towards the tip. With more weight at the end of the blade, chopping becomes forceful and efficient. A bolo has a full tang that makes it a sturdy chopping tool and weapon. The handle of a bolo could be made of hardwood or carabao horn and it may come with or without a guard.

Among Tagalogs, the bolo may be referred to as “itak.”

Being an agricultural country, the bolo is ubiquitous in the lives of Filipinos particularly those living in the countryside. It is an all-purpose tool that can be used in clearing bushes, chopping wood and tilling the soil. And when a self-defense situation arises, the bolo comes in handy as a formidable weapon.

In the Philippines, one can easily buy a bolo either from wet markets or street peddlers. But those who want a high quality piece could go to a “panday” (blacksmith) and have his bolo custom-made.

The venerable Katipunan and the 1896 Philippine Revolution against Spain would always be remembered with the image of Andres Bonifacio wielding a bolo. Despite the advance military technology of the United States during the Philippine-American War, Filipino bolomen remained to be a force to reckon with.

Orllino Ochosa’s book “Bandoleros: The Outlawed Guerillas of the Philippine-American War of 1903-1907” made reference to a band of bolomen in Luzon called the “Arma Blanca,” it reads, “Manila’s ‘Arma Blanca,’ that phantom army of bolomen whom General Luna had so much depended upon in his bold attack of Manila at the start of the war with the Americans.”

But it was during the Second World War that much documentation had been made on the exploits of Filipino bolomen.

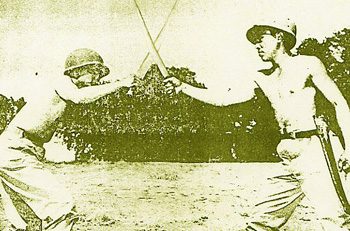

Filipino soldiers during WW II practicing bolo techniques.

The 1st Filipino Regiment of the United States Army in the Philippines during World War II holds the distinction of being labeled the original “Bolo Battalion.” Dan Inosanto in his book “The Filipino Martial Arts” mentioned how this fearless band of blade fighters came about, it says, “The young Filipino enlistees were soon disenchanted.

In the inimitable way of military services, they were required to conform to the armed forces’ methods of close quarter combat. When they were finally given the chance to demonstrate their native arts, the order was remanded. Their demonstrations included bettering the self-defense bayonet instructors with long leaf-shaped bolo knives and sticks. Thereafter, all platoons of Filipinos were issued bolo knives and they practiced their own arts in basic training.”

Among those bolomen who lived to tell their experiences was the late escrima master Leo Giron. Giron, who had served as a soldier of the US Army and fought in the jungles of the Philippines during World War II recounted his experiences fighting with a bolo in Mark Wiley’s Book “Filipino Martial Culture,” it says, “You develop a style without a style – chop, chop, chop.

One time I got clipped with a bayonet. I blocked the samurai sword coming down toward my shoulder, and a rifle bayonet went by my side from another Japanese shoulder. I cut the hip of the bayonet thruster and then the triceps of the one with the sword. After that I just keep charging and fighting the next ones. It’s up to the guys behind me to finish the job because there are too many more coming.”

On the recognition long overdue for the valiant bolomen of the Japanese occupation, Ambassador Roy A. Cimatu has the following words, “No one can deny the Boloman’s contribution to the intelligence backbone of the guerrilla resistance, or his masterful camouflage as meek villager by day, recon patrol by night. Yet, for all his courage and selflessness, the boloman remains a ghost—doomed to haunt the annals of military history in search of recognition.”

In 1998, the martial heritage of the 1st Bolo Battalion was reclaimed after the Philippine Marine Corps adapted as its official Close Quarters Combat/CQC doctrine the Pekiti-Tirsia system of Grand Tuhon Leo Gaje Jr.

An article titled “The Heritage of the Past and the Legacy of the Future” by Timothy D. Waid published in the November 1998 issue of Citemar6 the official publication of the Philippine Marine Corps reads, “In this year of the Republic of the Philippines National Centennial Celebration, 1998, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) reclaims it true martial heritage with the Philippine Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance Battalion designation as the modern BOLO BATTALION.

The Filipino Bolo has been the trademark combat weapon for generations of Filipino warriors and heroes from Datu Lapu Lapu to the founding fathers of the Katipunan and now of the Force Recon Marines.”

Mastery of the blade demands that its use become second nature. The Filipinos of the olden days were one with the blade because it is part and parcel of their existence. The bolo, which was the most popular knife at their disposal, was perceived as giver of life (being a farming implement) and a defender of life (being a self-defense weapon).