The tradition of becoming citizen-warriors is deeply rooted among Filipinos and its practice can be traced back in pre-hispanic times. The volatile condition of the Philippines during colonial times may have directly or indirectly affected the development of the Filipino martial arts (FMA) as constant threats from pirates and tulisanes (bandits) prompted many citizens then to take arms and form militia groups.

The perils posed by marauders created two opportunities for the dissemination of the FMA – for the masters, it is an occasion to teach their art for the noble purpose of defending the community. For the citizens, it is a chance to learn martial arts for free.

Among the most notable features of the FMA are simplicity and practicality. Under an able instructor, any average man or woman can become functional in the basics of the FMA in a very short period of time – the materials simply put can be learned today and used in the battlefield tomorrow.

For this, is simply the way things were in the olden days – in the event of an impending attack by another tribe, every able men in the community must be taught how to fight in the quickest possible time.

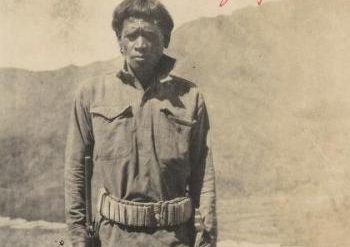

Ramiro Estalilla is among the old breed of escrimadors who have experienced the times when rural folks have used escrima to defend against the tulisanes. Estalilla’s recollections were published in Mark Wiley’s book Filipino Martial Culture, a part reads, “Since Mindanao was experiencing the ravages of war, training in armasan (the use of weapons) was open to everyone in the barrio (town) who wished to defend it against the many tulisanes (bandits). “Classes were very informal,” states Estalilla.

“The masters would demonstrate the techniques and anyone who was interested would get a partner and imitate the teacher. Someone would say ‘What if someone attacked you like this,’ then each master would show a counter and everyone would emulate his movements.”

For the immediate needs of the town’s people, training was limited to techniques in the use of the single and double sticks. Estalilla recalls that the practitioners from Zambales used shorter sticks, while those from Cotabato used longer ones.

The main concern of these masters, however, was not technical differences between the arts, but how to best instruct the people to defend themselves and their families.”

The viciousness and modus operandi of the tulisanes were chronicled even by foreign writers. Robert Mac Micking, in his 1851 book Recollections of Manilla and the Philippines, described how the bandits sowed terror among the people, “Were there a more numerous and efficient police force scattered over the country, none of the Spaniards would be afraid, as many of them now actually are, to live out of town, or to make distant excursions to the country, from fear of the tulisanes, or robber-bands, which are scattered about in various places, and are found pursuing their avocations in the neighborhood of the capital, although not so boldly as they did a few years since.

These robbers plunder the country in bands perfectly organized, and bodies of them are generally existing within a few miles of Manilla,—the wilds and forests of the Laguna being favourite haunts, as well as the shores of the Bay of Manilla, from which they can come by night, without leaving a trace of the direction they have taken, in bodies of ten and twenty men at a time, in a large banca.

They have apparently some friends in Manilla, who plan out their enterprises, send them intelligence, and direct their attacks; so that every now and then they are heard of as having gutted some rich native or Mestizo’s house in the suburbs of Manilla, after which they generally manage to get away clear before the alguacils come up.”

During Spanish colonial times, the threat of the tulisanes gave birth to the bantayanes or nightwatchmen. The root word of the term bantayanes is “bantay,” which is the Filipino word for sentry. The bantayanes were usually recruited from the native population with proven valor as the main qualification for entry. The bantayanes were ill-equipped armed only with native weapons like bancaos and sanduc-os or occasionally old guns.

Greg Bankoff, in Crime, Society, and the State in the Nineteenth-century Philippines depicts a vivid image of the bantayanes, “The system of nightwatchmen was extended to all towns and villages, where they were known by their Tagalog name of bantayanes. Records concerning membership of this corps are scant, but they continued to form the basis of village security into the nineteenth century and were occasionally mentioned in the diaries of visiting European travellers.

Bantayanes served as sentries at the approach to even the smallest settlements, where they were entrusted with keeping the streets illuminated and challenging passerby. Watchmen were furnished with bells to keep in contact with one another or to raise the alarm when necessary.

The seven or so men who composed the force in each settlement were recruited from the local inhabitant, armed with antiquated muskets or just lances, and commanded by an elective official, the alguacil mayor, who was under the orders of the gobernadorcillo.”