War is the prime stimulus in the development and refinement of man’s fighting skills. In the evolution of martial arts, it is good to note that spiritual and philosophical components usually progress during peaceful times while the creation of pragmatic fighting skills took place in the horrid conditions of the battlefield.

The Spaniards described the people of the Philippine islands as warlike when they first came to colonize the territory. “Kalis” was the natives’ term for fighting with bladed weapons and sticks. The word “kalis” was included in Vocabulario de la lengua Tagala, the first Tagalog-Spanish dictionary published in Laguna in 1613.

But it would also be of great interest to Filipino martial arts researchers that based on available historical and archaeological proofs, many parts of the Philippines may have had experienced periods of near absolute peace before maritime raids and wars between chiefdoms became the order of the day.

Laura Lee Junker in her book Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms, wrote that mortuary evidence from archaeological diggings in the country indicate that not a single burial from the complex society development period (500 BC to 1,000 AD) yielded osteological proof for violent death, and there are no recorded instances of mass burials.

To this, she added, “In contrast, significant number of the burials recovered from fifteenth-century cemetery such as Calatagan, Calubcub Segundo and Tanjay have unequivocal signs of violence, including decapitation, skeletal traumas or impaling of metal weapons.”

Particularly interesting among Lee’s points is her mention of how the intensifying conflict in the archipelago influenced warriorship. On this, she wrote, “Finally, linguistic analysis by Scott [William Henry Scott] has suggested that a class of militarily specialized warrior-elite encoded in the vocabulary in some Philippine complex societies (particularly the Tagalogs around Manila) are relatively recent development in response to escalating warfare in the archipelago, as evidenced in their designation by sixteenth-century Malay terms.”

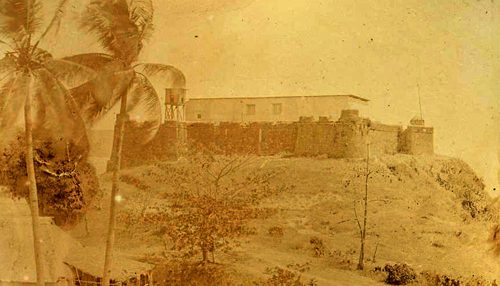

Lee noted that historical records and archaeological data suggest that the degree and intensity of interpolity raiding increased during the last 200 years just before European contact – the reason for this were economic and political expansion. She wrote of the nature of the fortifications in the islands before the aforementioned period to highlight the amount of change that had occurred.

“In addition, descriptions of fortifications and other large-scale defensive works are noticeably absent from fourteenth-century and earlier Chinese accounts of Philippine coastal trading centers, and in several instances it is implied that the chiefly residences and storehouses were readily visible from sea approaches.

Filipino chiefs who were wary of foreign ships are described as disappearing inland, rather than taking refuge inside fortified coastal towns.”

Kuta and bangbang

Lee wrote of the structure and construction of early Filipino fortifications based on Spanish accounts, “Spanish description indicates that the typical fortifications consisted of raised earthworks with wooden palisade along the top (called a “kuta” in Tagalog) surrounded by a ditch or water-filled moat (bangbang in Tagalog).

However, local variations on construction techniques were specific to the local environment, geography and intensity of conflict. In Bicol (southeastern Luzon), bamboo towers called “bantara’ were built behind the fortifications as stands for archers armed with long bows.

Fortified villages on the Zamboanga peninsula (within the Sulu polity) constructed a high bamboo watchtower outside the fortifications so that warriors could scan the sea for approaching marauders.”

While the natives soon perfected the art of fortification, not all barangays could afford to construct one due to the massive labor force it required. And even if a chiefdom managed to build a fortification, it would be incomplete without an army of warriors to man it. This problem gave rise to alternative strategies that Lee mentioned in her book.

“For many Philippine polities (particularly small-scale ones), the labor investment necessary to construct and defend fortifications may have been too costly.

Rather than lose labor to this type of massive construction or to warfare deaths, it is likely that many groups adopted the strategy of temporarily abandoning a town with portable valuables in tow to return when the marauders left with their scavenged booty.

Early Spanish accounts suggest that these refuges could be naturally defensible positions near the coastal settlement, as evidenced by the Visayan terms ‘moog,” “ili,” and “ilihan,” which are translated as a rocky outcropping or natural pinnacle that could be fortified and used as a refuge to which villagers could be evacuated.

“Scott [William Henry Scott] notes that Spanish writings and lithographs from the sixteenth century depict wooden “tree houses” constructed around a stout tree or freestanding on thick pilings and sometimes reaching more than fifteen meters off the ground.

These were claimed to have functioned only in situations of warfare as refuges, and they were reached by a vine that could be pulled up. The paths approaching these tree houses as well as other refuges were frequently planted with traps and poisoned stakes to catch the unwary enemy.”